The What-If Machine: Can AI Agents Accurately Simulate Human Behavior?

_New research shows that AI agents, powered by large language models and rich qualitative data, can replicate human attitudes and behaviors with surprising accu...

New research shows that AI agents, powered by large language models and rich qualitative data, can replicate human attitudes and behaviors with surprising accuracy—offering a powerful new tool for decision-making.

Published: 2025-11-15

Summary

Leaders, policymakers, and researchers constantly make high-stakes decisions with incomplete information about how people will react. What if you had a 'what-if machine'—a way to simulate human responses to a new product, policy, or strategy before launch? For decades, this has been the realm of simplified, rigid simulations. But a new frontier is emerging with 'generative agents,' AI systems powered by large language models (LLMs) that can simulate human behavior with unprecedented nuance. Groundbreaking research from Stanford University demonstrates that when these agents are built on rich, qualitative data from in-depth interviews, they can replicate human attitudes and behaviors with remarkable accuracy. This article explores the architecture behind these digital doppelgängers, the rigorous methods used to validate their accuracy, and a practical framework for using them responsibly. By understanding both their immense potential and their current limitations, we can begin to harness these tools to make better, more informed decisions in a complex world.

Key Takeaways

- Traditional decision-making is hampered by incomplete information, leading to costly miscalculations.

- Generative agents, powered by LLMs, offer a new paradigm for simulating complex human behavior, moving beyond the rigid rules of older agent-based models.

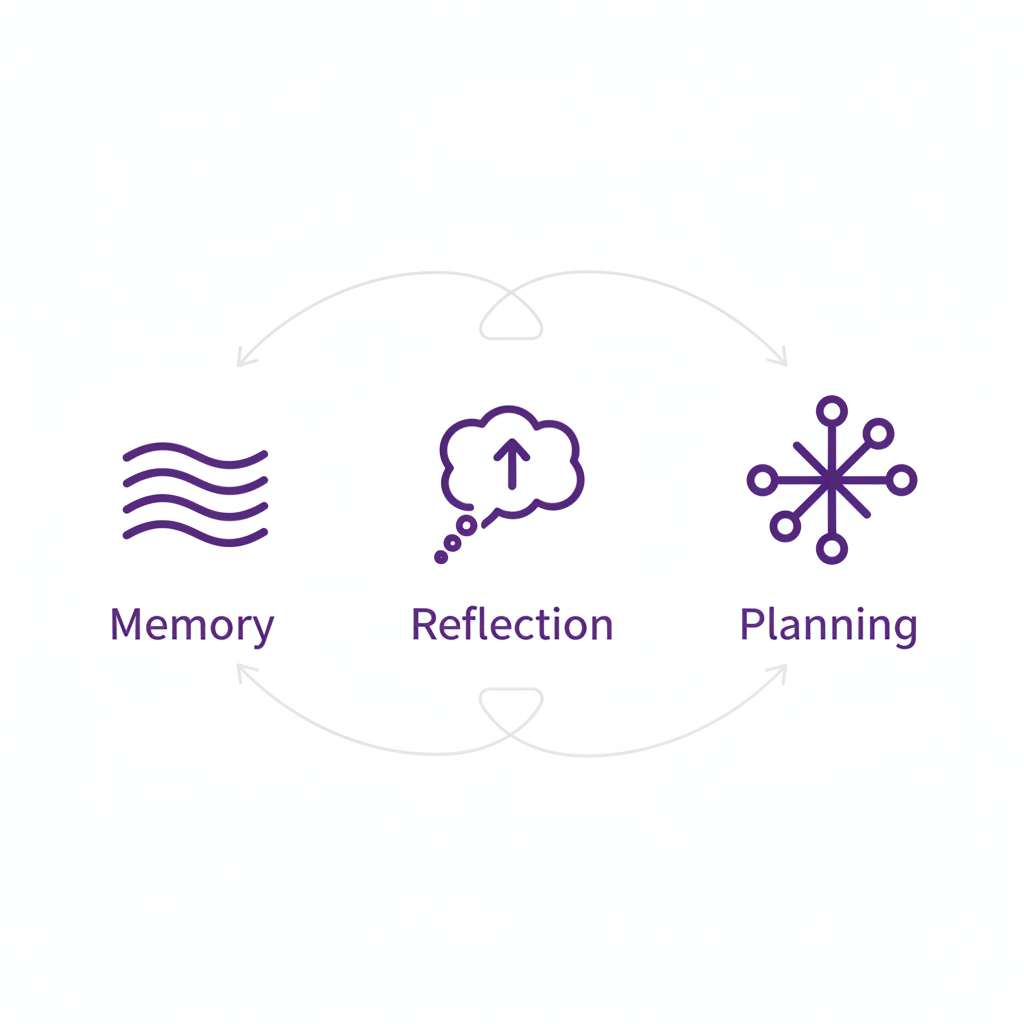

- The architecture of a believable agent relies on three pillars: a detailed memory stream, a mechanism for reflection to form higher-level insights, and the ability to plan and adapt.

- The key to accuracy is data quality. Agents built from rich, qualitative interviews replicate human survey responses up to 85% as accurately as humans replicate themselves, far outperforming agents based on simple demographics.

- This high-fidelity simulation can reduce stereotyping and bias by capturing the nuance of individual experience rather than relying on broad categories.

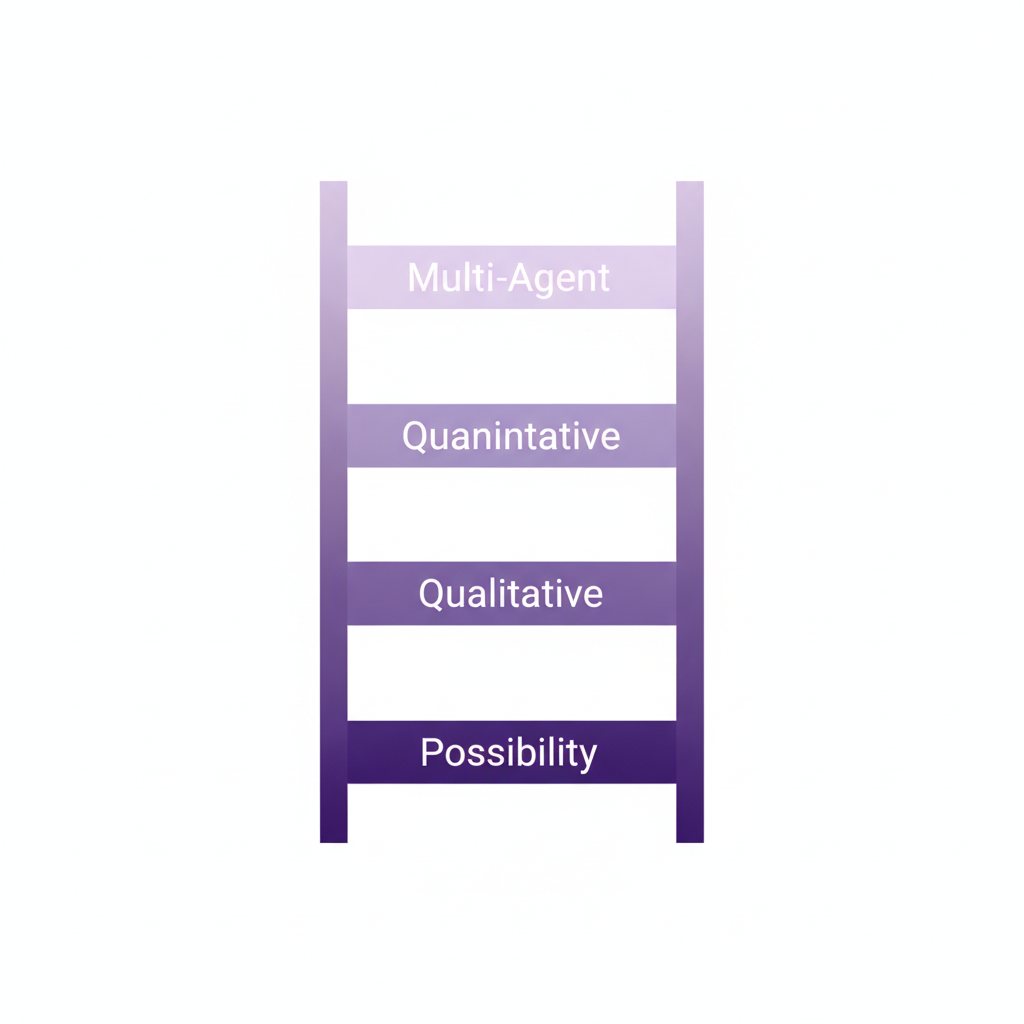

- A 'Ladder of Trust' provides a risk framework: use simulations confidently for exploring possibilities and qualitative attitudes, but exercise caution with precise quantitative predictions and complex multi-agent dynamics.

- Practical applications are already emerging in areas like pre-launch policy testing for online communities ('look before you launch'), soft skills training, and a new generation of market research.

- While not a replacement for real-world engagement, AI simulation is a powerful tool for narrowing options, stress-testing ideas, and augmenting human judgment.

Article

The Perennial Problem of the Unknown

Every significant decision—whether launching a product, setting a policy, or managing a team—is a bet on the future. We make these bets based on the best data we can gather, but that data is almost always incomplete. How will customers react? How will a new policy affect community dynamics? What unintended consequences might arise?

This uncertainty is not a new problem. In 1936, the sociologist Robert K. Merton famously detailed the "unanticipated consequences of purposive social action," showing how even well-intentioned plans can backfire in complex social systems [3, 11, 15]. We all want to escape the city for a quiet holiday, only to find that everyone else had the same idea, creating a new crowd in the wilderness. We act on our best guess, but the feedback loop is slow and expensive; you can only launch a product or enact a policy once.

What if you could de-risk these decisions? What if you had a “what-if machine”—a tool to explore the plausible futures of your choices before committing to one? For years, this has been a tantalizing prospect, but the technology has now arrived at a critical inflection point. A new frontier of artificial intelligence, known as generative agents, promises to create sophisticated and, crucially, accurate simulations of human behavior.

Generative agents offer a way to explore the potential outcomes of decisions before they are made.

From Simple Rules to Rich Personas: A Brief History of Simulation

The idea of simulating human societies is not new. In the 1970s, Nobel laureate Thomas Schelling developed early agent-based models (ABMs) to explore social dynamics [5, 6, 27]. His famous model showed how a highly segregated society could emerge even if its individual inhabitants held only a mild preference for living near people like themselves. These models, which are still in use, represent people as simple algorithms following a few basic rules.

But their simplicity is also their weakness. Reducing a person to a handful of parameters or a rigid script—if punched, then get mad—creates a stylized, brittle simulation. As a result, traditional ABMs have often been seen as insightful but have had minimal impact on real-world decision-making. They couldn't capture the messy, surprising, and context-rich nature of human behavior.

This is where Large Language Models (LLMs)—the technology behind tools like ChatGPT—change the game. Trained on vast archives of human text, from books and research papers to social media conversations, these models have absorbed an immense amount of information about how people think, feel, and interact. Researchers realized they could prompt an LLM to adopt a specific persona, complete with a unique background, personality, and set of experiences, creating a far more nuanced and believable digital actor.

Inside the Mind of a Digital Human

To test this idea, a team of Stanford University researchers created a virtual town called Smallville, populated by 25 autonomous generative agents [13, 32, 39]. Each agent was given a name, a job, and a set of relationships. The artist in town would wake up and paint; the college student would sleep in and then work on his music theory composition. They weren't following a script; their actions emerged from their identity and their interactions with the world and each other.

In one experiment, the researchers gave a single agent, Isabella, the simple intention to host a Valentine's Day party. From that one seed, a cascade of believable social behaviors unfolded. Isabella invited friends, who then invited others. She coordinated with another agent to decorate the café. By the day of the party, half the town had heard about it, and five agents showed up—a plausible outcome for a last-minute event. One agent even asked her crush to the party. Nothing in the AI's architecture was a "party-planning module"; this complex social coordination emerged organically.

The Architecture of a Generative Agent

How is this possible? These agents are built on an architecture designed to mimic human cognition, resting on three key pillars:

-

Memory and Retrieval: Each agent maintains a memory stream, a comprehensive log of everything it observes and does. Because this log can become enormous, the system uses a technique called Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG). When deciding what to do next, the agent doesn't read its entire life story. Instead, it performs a search over its memories, prioritizing those that are recent, important, and relevant to the current situation. This is akin to how our own minds surface relevant thoughts and memories in the moment.

-

Reflection: Humans don't just record experiences; we synthesize them into higher-level insights. The agents do this through reflection. Periodically, the system prompts the agent to look at a cluster of recent memories and draw a more abstract conclusion. For example, observing that an agent named Klaus has been reading about gentrification and urban design might lead to the reflection, "Klaus spends a lot of time reading." These reflections are stored back in the memory stream, allowing the agent to build a more coherent sense of self and its goals over time.

-

Planning: To maintain believability over long periods, agents need to plan. They start with a broad plan for the day, then break it down into hour-by-hour and minute-by-minute actions. Crucially, these plans are not set in stone. If an agent observes something unexpected—like seeing their son walking by their workplace—it can react and replan its actions accordingly.

The architecture of a generative agent combines memory, reflection, and planning to produce believable, adaptive behavior.

The Billion-Dollar Question: Is It Real or Just a Good Story?

Smallville demonstrated that generative agents could be believable. But for a what-if machine to be useful, it needs to be more than that—it needs to be accurate. A Disney character is believable, but you wouldn't base a billion-dollar product launch on how Mickey Mouse might react. The central challenge is moving from compelling fiction to predictive fact.

From Believability to Accuracy

Early attempts to create accurate agents often relied on simple demographic profiles (e.g., "35-year-old male, lives in California, works in tech"). But this approach can easily fall into stereotypes. If you tell a model that someone is from South Korea, it might stereotypically predict they'll eat rice for lunch, missing the vast diversity of individual preferences.

To overcome this, the same Stanford research team embarked on a far more ambitious validation study [7, 33, 43]. They hypothesized that the key to accuracy was not demographics, but rich, qualitative data that captures the story of a person's life.

A Groundbreaking Validation Experiment

The researchers partnered with the American Voices Project, a Stanford initiative that conducts in-depth, two-hour interviews with a representative sample of Americans [17, 28, 38]. These interviews cover everything from life stories and community ties to finances and health.

The team used these interview transcripts to create 1,000 "digital twins"—generative agents whose core memory was the life experience of a real person. They then conducted a parallel experiment:

- Humans: The 1,000 real participants took a battery of well-established surveys and experiments, including the General Social Survey (GSS), a cornerstone of American social science for 50 years [10, 22, 23].

- Agents: Their corresponding digital twins were given the exact same surveys and experiments.

The goal was to measure how closely an agent's answers matched the answers of its human counterpart. To set a realistic benchmark, the researchers had the real humans take the surveys twice, two weeks apart. After all, even people aren't perfectly consistent. The ultimate measure of success was how well the agents could replicate a person's responses compared to how well that person replicated their own responses over time.

The Surprising Results

The findings were striking. Agents based on the full interviews replicated people's responses on the General Social Survey 85% as accurately as the people replicated themselves [7, 33]. This was a massive leap over agents based on simple demographics, which scored around 70%.

Studies show that agents built on rich interview data can replicate human survey responses with high fidelity.

This high accuracy held across a range of tasks, including personality tests and behavioral economic games. Furthermore, the rich interview data helped mitigate bias. When an agent only knows a person's political affiliation, it tends to produce stereotyped responses. But with the full context of their life story, the model's predictions become far more nuanced and less prone to caricature.

In a final, powerful test, the agents were asked to replicate five published scientific experiments. They successfully replicated the results of four. The fifth study they failed to replicate—but so did the 1,000 real human participants. The simulation correctly predicted that the original study was likely bad science and its effect wasn't real. This has been corroborated by related work from Stanford professor Rob Willer, who found that LLM simulations could predict the effect sizes of unpublished experiments with a correlation of up to 0.9 [2, 18].

A Practical Guide to Building Your Own 'What-If Machine'

This technology is rapidly moving from academic labs to practical application, with venture capital firms like Andreessen Horowitz highlighting its potential to reinvent fields like market research [4, 9, 19]. For any organization looking to explore this, the key is to approach it with both ambition and a healthy dose of scientific rigor.

The Data Diet of an AI Agent

The research offers a clear lesson: the quality of a simulation depends entirely on the quality of its input data.

- Bad: Defining an agent with a single demographic variable (e.g., "be a conservative"). This is a recipe for stereotyping and produces unreliable results.

- Okay: Using five or six demographic variables. This is better and can achieve moderate accuracy (~70% replication ratio), but still misses individual variance.

- Best: Using rich, qualitative data like interviews. Surprisingly, the researchers found that even a randomly sampled 20% of the two-hour interview retained most of the predictive power, as long as the remaining data was relevant to the questions being asked. You can't interview someone only about fashion and expect to accurately predict their retirement planning.

Organizations may already have a treasure trove of this data in the form of user research interviews, customer support transcripts, or ethnographic studies.

The Ladder of Trust: Knowing When to Rely on Simulation

This is a new and powerful method, and it's critical not to over-trust it. A useful mental model is a "ladder of trust," where each rung represents a more ambitious—and riskier—use of simulation.

The 'Ladder of Trust' helps calibrate confidence in simulation results based on the complexity of the task.

-

Possibility (Low Risk): At the bottom rung, simulation is used to ask, "What could happen?" The goal is not to predict probabilities but to identify plausible scenarios, especially negative ones. This is excellent for stress-testing ideas. This generally works today.

-

Qualitative Outcomes (Medium Risk): The next rung focuses on predicting attitudes, opinions, and conversational responses. How might people feel about a new feature? What concerns might they raise? With rich data, this mostly works today and can provide a strong directional sense of public sentiment.

-

Quantitative Outcomes (High Risk): This involves predicting precise numbers—histograms, market share percentages, or survey bar charts. Here, errors can be significant. The difference between 13% and 1.2% of users being familiar with a feature could change a business decision. This rung should be used with caution, primarily to narrow down a wide set of options to a few promising candidates for real-world A/B testing.

-

Multi-Agent Simulation (Very High Risk): At the top of the ladder is simulating an entire market or community with interacting agents. The emergent dynamics can be insightful but are also highly sensitive to initial assumptions. Trusting these complex outcomes requires validating every individual agent's accuracy, a bar that is currently very high. Tread very carefully here.

Why It Matters: The New Frontiers of Simulation

When used responsibly within this framework, generative agents open up powerful new applications.

Online community designers can use them to "look before you launch," simulating how a new moderation policy might be exploited by trolls before it goes live. This allows them to build more resilient systems from day one, rather than constantly reacting to dumpster fires.

Another promising area is soft skills training. Researchers have built systems where users can practice difficult conversations, like a salary negotiation or a conflict resolution, with an AI agent. In one study, users who practiced with a simulation were two-thirds less likely to use an antisocial strategy in a real conflict later on.

This is not about replacing human judgment, but augmenting it. It's about making our intuition faster, our foresight sharper, and our decisions more robust. The what-if machine is no longer science fiction. It's a tool that, if wielded with care and intellectual honesty, can help us navigate an uncertain future with a little more clarity.

Citations

- Generative Agents: Interactive Simulacra of Human Behavior - arXiv (whitepaper, 2023-04-07) https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.03442

- The foundational paper describing the 'Smallville' experiment and the architecture of generative agents (memory, reflection, planning).

- Social science researchers use AI to simulate human subjects - Stanford Report (news, 2025-07-29) https://stanford.io/3Vw8ZkL

- Summarizes research by Rob Willer and colleagues at Stanford showing LLMs can predict the results of randomized controlled trials with high accuracy (0.85 correlation).

- The Unanticipated Consequences of Purposive Social Action - American Sociological Review (journal, 1936-12-01) https://www.jstor.org/stable/2084615

- The seminal paper by Robert K. Merton that introduced the concept of unintended consequences, providing historical context for the problem simulations aim to solve. Corrects the speaker's reference of 1906.

- Faster, Smarter, Cheaper: AI Is Reinventing Market Research - Andreessen Horowitz (a16z) (news, 2025-06-03) https://a16z.com/faster-smarter-cheaper-ai-is-reinventing-market-research/

- An influential article from a major venture capital firm arguing that generative agents are the next frontier for market research, citing the Stanford research.

- Dynamic models of segregation - Journal of Mathematical Sociology (journal, 1971-07-01) https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0022250X.1971.9989794

- One of Thomas Schelling's original papers on agent-based models of segregation, establishing the historical baseline for this type of simulation.

- Micromotives and Macrobehavior - W. W. Norton & Company (book, 1978-01-01) https://wwnorton.com/books/9780393329469

- Schelling's foundational book that expanded on his agent-based models, explaining how individual choices aggregate into large-scale, often unintended, social patterns.

- Simulating Human Behavior with AI Agents - Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI) (org, 2025-05-20) https://hai.stanford.edu/news/simulating-human-behavior-ai-agents

- Primary source summary of the 1,000-person validation study, detailing the methodology and the 85% accuracy finding.

- Do Large Language Models Solve the Problems of Agent-Based Modeling? A Critical Review of Generative Social Simulations - arXiv (whitepaper, 2025-04-04) https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.03274

- Provides a critical perspective, arguing that LLMs may exacerbate some long-standing challenges of ABMs, such as validation and the 'black-box' nature of the models. Important for nuance and limitations.

- AI Agents Simulate 1052 Individuals' Personalities with Impressive Accuracy - Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI) (org, 2025-01-21) https://hai.stanford.edu/news/ai-agents-simulate-1052-individuals-personalities-impressive-accuracy

- Provides further details on the validation study, including the replication of five social science experiments and the ethical guardrails considered by the research team.

- General Social Survey (GSS) - NORC at the University of Chicago (dataset, 2025-01-01) https://gss.norc.org/

- Official website for the General Social Survey, the benchmark dataset used in the validation study to measure agent accuracy against real human responses.

- Unintended consequences - Wikipedia (documentation, 2025-10-27) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unintended_consequences

- Provides an accessible overview of Robert K. Merton's concept and its history in social science.

- The What-If Machine: The Promise and Peril of AI Counterfactuals - Stanford Graduate School of Business (video, 2024-10-08)

- The original video presentation that this article is based on.

- LLM-Based Social Simulations Require a Boundary - arXiv (whitepaper, 2025-06-24) https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.19806

- A position paper arguing for clear boundaries on the use of LLM simulations, noting their tendency toward an 'average persona' and lack of behavioral heterogeneity, which supports the 'Ladder of Trust' concept.

- American Voices Project - Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality (org, 2025-01-01) https://inequality.stanford.edu/projects/american-voices-project

- Official page for the American Voices Project, the source of the rich qualitative interview data used to create the high-fidelity 'digital twin' agents.

Appendices

Glossary

- Agent-Based Model (ABM): A computational model that simulates the actions and interactions of autonomous agents (both individual and collective entities) to assess their effects on the system as a whole. Traditional ABMs use simple, predefined rules for agents.

- Generative Agent: An advanced type of computational agent that uses a large language model (LLM) as its core engine, supplemented with memory, reflection, and planning capabilities, to simulate believable and complex human behavior.

- Large Language Model (LLM): A type of artificial intelligence model trained on vast amounts of text data, enabling it to understand, generate, and respond to human language in a nuanced, context-aware manner.

- Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG): An AI technique that enhances an LLM's responses by first retrieving relevant information from an external knowledge base (like an agent's memory stream) and providing it to the model as context for its generation.

Contrarian Views

- Some researchers argue that while generative agents are believable, they may primarily reflect the 'average' or most common behaviors found in the LLM's training data, failing to capture the full spectrum of human eccentricity and variance, which is critical for modeling social dynamics [13, 20].

- Critics caution that the 'black-box' nature of LLMs makes it difficult to understand the causal mechanisms behind an agent's behavior, potentially limiting the scientific value of the simulations for theory-building compared to more transparent, rule-based models .

- There is a significant risk of over-anthropomorphizing these agents. Researchers must be careful to remember that any results are descriptive of the model's behavior, not a direct, causal model of human cognition. The link is correlational, not causal .

Limitations

- The accuracy of generative agents is highly dependent on the quality and relevance of the initial data used to create their personas. Biased or incomplete data will lead to biased and inaccurate simulations.

- Current validation methods are robust for individual attitudes but less so for complex, emergent group dynamics. The accuracy of multi-agent simulations is still an open and challenging research question.

- LLMs can still 'hallucinate' or produce inconsistent behavior, especially over long time horizons. Ensuring agent coherence and robustness remains a technical challenge [25, 46].

- The ethical implications are significant, including data privacy for the individuals whose interviews are used, the potential for misuse in creating manipulative technologies, and the risk of over-reliance on simulations for high-stakes decisions [21, 43].

Further Reading

- Generative Agents: Interactive Simulacra of Human Behavior - https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.03442

- Simulating Human Behavior with AI Agents (Stanford HAI) - https://hai.stanford.edu/news/simulating-human-behavior-ai-agents

- Micromotives and Macrobehavior (Thomas C. Schelling, 1978) - https://wwnorton.com/books/9780393329469

Recommended Resources

- Signal and Intent: A publication that decodes the timeless human intent behind today's technological signal.

- Blue Lens Research: AI-powered patient research platform for healthcare, ensuring compliance and deep, actionable insights.

- Outcomes Atlas: Your Atlas to Outcomes — mapping impact and gathering beneficiary feedback for nonprofits to scale without adding staff.

- Lean Signal: Customer insights at startup speed — validating product-market fit with rapid, AI-powered qualitative research.

- Qualz.ai: Transforming qualitative research with an AI co-pilot designed to streamline data collection and analysis.

Ready to transform your research practice?

See how Thesis Strategies can accelerate your next engagement.